Click here to read about the book.

Excerpts from...

HIGH FIVES, PENNANT DRIVES, AND FERNANDOMANIA:

A FAN'S HISTORY OF THE LOS ANGELES DODGERS' GLORY YEARS (1977-1981)

Copyright (c) 2012 - Paul Haddad / Santa Monica Press

INTRODUCTION:

Leading Off

My first introduction to the Dodgers was one of heartbreak. The perpetrator was Reggie Jackson. His crime, by now legendary, was three successive home runs in the deciding game of the 1977 World Series. I had followed the Dodgers from afar for most of my first 11 years, even attending a couple games at Dodger Stadium with my summer camp. But I never understood what it meant to be a fan until that moment.

Outside of my dad betting on football and playing the horses, I grew up in a household that was largely indifferent to professional sports teams. I never even played Little League. As a result, baseball and I were relative strangers. I didn’t understand the nuances and rhythms of the game, and I lacked that mentor who might explain the strategy behind a hit-and-run, how to keep a scorecard, or what a sacrifice fly was. ERA? I didn’t know an Earned Run Average from an Equal Rights Amendment. And if you were talking about the Penguin, my mind flashed, “Batman,” not “Ron Cey.”

But the seeds of my Dodger fandom began to bear fruit in that ’77 Fall Classic. It’s hard to say what triggered my obsession with the team sporting crisp white uniforms with red numbers and blue trim. It was probably an accumulation of things leading up to the Series. With the Dodgers making the playoffs, Mom had started following the games on the radio. I remember one day she picked me up from school, and she was listening to the third game of the NLCS against the Phillies. Burt Hooton had just gotten pulled in the second inning after walking three batters in a row with the bases loaded. Mom’s first words to me when I got into the car were: “Burt Hooton just lost his cool.” I had never heard that phrase before, and I was intrigued. How does one lose his “cool,” and if he does, can he ever get it back? I thought of the Fonz on Happy Days and could never imagine that happening to him.

There was also a palpable buzz in Los Angeles surrounding the Dodgers getting into the postseason, an excitement that trickled down to the schoolyard and classrooms at West Hollywood Elementary. On the eve of the World Series, a fellow sixth grader named Trevor asked me if I wanted to make a bet on Game 1. After careful consideration, I passed on his fifty-cent wager. I couldn’t rationalize risking money earmarked for cherry Now-N-Laters on a sport I was only now beginning to understand. By the third game, Trevor dropped his bet to a quarter. Perhaps sensing a sucker, he even let me pick the team. I caved and chose the Dodgers, knowing that Game 3 would be played at home. The Dodgers answered my loyalty by losing 5–3.

All of this set the stage for the deciding Game 6 at Yankee Stadium. New York held a one-game edge, three games to two. For the first time in my life, I sat down in front of the TV to watch a game from start to finish. By this point, my mom, dad, and older brother, Michael, were invested in the series. The Dodgers had just shellacked the Yankees in Game 5, once leading 10–0 to seemingly recapture the momentum, and there was every reason to believe they would win Game 6 and force a deciding Game 7. I remember we were allowed to eat dinner on TV trays in the den so we could take in the broadcast on our giant Zenith set. Even though I didn’t have any money riding on the game, I was inexplicably nervous and fidgety, pacing the room like a recovering smoker. Suddenly, the Dodgers’ battle had become my battle—this was personal.

At this point I should probably mention that I have always had a notorious competitive streak. It pains me to admit it, but my parents have Super 8 footage of me throwing an epic tantrum while playing miniature golf with three friends on my eighth birthday. By the final hole, I am bringing up the rear, at which point I raise my pee-wee club and pummel an unsuspecting windmill as if it were a piñata. This would also explain why I detested tennis player John McEnroe when he came on the scene. His antics reminded me too much of myself.

The Dodgers got out to an early 2–0 lead in that sixth game, thanks to a two-run triple by my future idol, Steve Garvey. Things were looking good. L.A. held a 3–2 lead going into the bottom of the fourth, when suddenly any hope of forcing a Game 7 began to dissipate. Mr. October saw to that himself, crushing the first of three home runs. The pitcher? Burt Hooton, looking about as cool as Dustin Hoffman in that dental chair in Marathon Man. By the time Reggie stepped up in the eighth inning, the crowd’s chants of “Reg-GIE, Reg-GIE, Reg-GIE” were like ice picks in my ears. His third home run—an estimated 475-foot blast on the first pitch—cut into my skull.

“Oh, what a blow!” gushed Howard Cosell on TV. “What a way to top it off!”

Clutching my ears, I tore out of the den and collapsed in a heap of rage in my bedroom, thrashing my elbows against the floor. I hated Reggie Jackson, with his cocksure grin and streetwise swagger. I wanted to throttle him. He had made the Dodgers look like a Wiffle ball team, swatting three homers with a flick of his wrist, hop-skipping around the bases before flashing “Hi, Moms” to the camera as he unfurled another digit for each homer. Who did he think he was, anyway? At some point my mother came in and tried to calm me down, but I would have none of it. I was inconsolable. I had lost my cool.

And I was hooked.

Because you’re reading this book, you too probably remember what it felt like to fall for the Los Angeles Dodgers. If you’re like most, your devotion was fashioned around happy, random moments, like jostling along Dodger Stadium at field level for an autograph from your favorite player, or witnessing a momentous home run as you ripped into your double-bag of salted-in-the-shell peanuts. Or perhaps it was Vin Scully lulling you to sleep on your transistor radio, or the ritual of you and Dad pulling up a chair in front of KTTV Channel 11 to catch a game. Before you knew it, they had you hooked, too. Not just on the Dodgers, but on baseball. For me, the Dodgers and baseball struck like a double lightning bolt, not unlike falling in love at first sight. Even Reggie Jackson couldn’t squelch their power—in fact, he only amplified it. For just like your first love, who may rip your heart into a thousand pieces before liquefying it in a blender for good measure, you never get over that feeling. And yet all of us keep coming back for more, enduring years of torment for those rare, fleeting moments of pure bliss. Baseball proves the old axiom: It’s better to have loved and lost, than to not have loved at all.

...

On the cusp of the ’78 season, I was so pumped for Dodger baseball, I resolved to record every inning of every game (minus weekday games when I was in school or other special circumstances). Michael reminded me that an average game took two and a half hours to play. At that rate, I’d run out of our stock of Scotch brand tapes sometime in mid-April. This shortcoming led to an even more brilliant idea. Why not do a sort of “greatest hits” tape, much like musical acts do on albums? To do this, I would need to record games in their entirety, then transfer all the best home runs to another tape using a second cassette recorder. Once all the highlights were dubbed to this second tape, I would simply record over the raw tapes for the next day’s game, continuing this process throughout the season. By the end of the year, I would have cataloged the best moments of the Dodgers’ 1978 season, hopefully culminating in a World Series Championship that had eluded them the year before. I would call the finished tape Homerun Highlights. (It wasn’t till later in ’78 that I realized “Home Run” should be two words, but by that point I had devised a logo in which I had spelled it out as one word.)

On April 7, 1978, I recorded my first Dodger game off the radio. It was the team’s opener against the Braves at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. The Dodgers crushed them, 13–4. Davey Lopes and Rick Monday hit home runs. My obsession with cataloging the Dodgers’ greatest offensive highlights was officially born.

Little did I know it wouldn’t end until four seasons—and ten 90-minute tapes—later.

...

1st INNING:

April - June 1978

The Case for Garvey

Like many kids in the 1970s, I was a fan of the ABC Saturday morning cartoon series Super Friends, in which Superman, Wonder Woman, Batman, Aquaman, and other DC Comics icons rallied together as a sort of United Nations of Superheroes. Though I admired the unique talents each superhero brought to the table, they all had limitations. I mean, was Aquaman really any more threatening than me when he was out of the water? How many crimes actually took place deep in the ocean? (More than one might think, apparently.) Barring his nagging weakness against kryptonite, Superman was the only superhero whose powers were truly super, possessing all of his friends’ talents and then some. Superman ruled. Or so I thought.

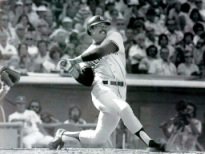

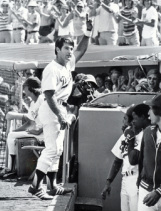

Steve Garvey was not Superman, but we could be forgiven for thinking he was, because he was one heck of an understudy. At 25 years old, Steve enjoyed a breakout season in 1974, when he won the National League’s Most Valuable Player award and was the write-in starting first baseman for the All-Star Game (and rewarded his fans’ faith in him by claiming that MVP trophy as well). The Garvey Mystique is legendary. He was already bleeding Dodger blue as a child, when he was a bat boy for the Brooklyn Dodgers in spring training, where his father was a bus driver hired by the team. To this day, nobody has ever looked better in the Dodgers’ home whites. Garvey’s chiseled face and Brylcreemed block of jet-black hair were truly the sort of things that could only spring from the pen of a comic book artist. His body was defined by Popeye-esque forearms and muscular thighs, with movements that were purposeful, smooth, and deliberate. Just as there was never a hair out of place when he hit, ran, or fielded, there seemed to be never a movement out of place, either. He was a model of consistency and durability, almost machine-like, developing the nickname “Iron Man.” Iron or steel, when you added up the whole impossible package, that was Steve Garvey, whose sum total truly seemed like Clark Kent’s doppelganger.

As an impressionable youngster looking for heroes, I fell hard under the spell of the Garvey Mystique. I was not alone. He was also the favorite player of my brother, Michael, and most boys I knew. I never bothered getting his autograph before games because the crowd was always too big. By 1977, Garvey’s clean-cut image had elevated him to mega-role model status, resulting in a junior high school named after him in Lindsay, California. In 1978, he was the first player to rack up more than four million votes for the All-Star Game. Garvey repaid the fans by winning the All-Star MVP Award. He popped up in Aqua Cologne commercials and on Fantasy Island. He was crowned with a new nickname—“Senator”—a nod to the promising political career that no doubt loomed in his future. In 1981, he was included in a coffee-table book that I still have to this day: The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time.

But behind the scenes, Garvey was dealing with his own kryptonite—teammates resentful of his popularity, troubles at home with his wife, Cyndy, and later, paternity suits brought against him after his own marriage dissolved.

There’s an old adage in baseball: “You’re only as good as your last at-bat.” The public’s lasting impression of Garvey was not the day he walked off the field as a San Diego Padre in May of 1987, but his admission that he fathered two children out of wedlock to two separate women in 1989. That same year, Cyndy, then his ex-wife, published a scathing tell-all book that exposed the alleged dark side of Steve Garvey.

I cannot overemphasize the repercussions all this had on Garvey’s legacy at that time. Overnight, he became a national punch line. (Anyone remember those “Steve Garvey Is Not My Padre” bumper stickers?) Garvey’s first year of eligibility for the Hall of Fame was in 1993. Needing 75 percent of the votes by the Baseball Writers Association of America for induction, Steve garnered just 41.6 percent. In 2007, his last year of eligibility, his vote count had shriveled to a paltry 21 percent.

So how did this “future Hall of Famer,” as he was so often referred to in his playing days, lose his Get Into Hall Free card? It’s a question many have pondered. I believe there are three main reasons why the Baseball Writers shut Garvey out of the Hall.

...

Steve Garvey was not Superman, but we could be forgiven for thinking he was, because he was one heck of an understudy. At 25 years old, Steve enjoyed a breakout season in 1974, when he won the National League’s Most Valuable Player award and was the write-in starting first baseman for the All-Star Game (and rewarded his fans’ faith in him by claiming that MVP trophy as well). The Garvey Mystique is legendary. He was already bleeding Dodger blue as a child, when he was a bat boy for the Brooklyn Dodgers in spring training, where his father was a bus driver hired by the team. To this day, nobody has ever looked better in the Dodgers’ home whites. Garvey’s chiseled face and Brylcreemed block of jet-black hair were truly the sort of things that could only spring from the pen of a comic book artist. His body was defined by Popeye-esque forearms and muscular thighs, with movements that were purposeful, smooth, and deliberate. Just as there was never a hair out of place when he hit, ran, or fielded, there seemed to be never a movement out of place, either. He was a model of consistency and durability, almost machine-like, developing the nickname “Iron Man.” Iron or steel, when you added up the whole impossible package, that was Steve Garvey, whose sum total truly seemed like Clark Kent’s doppelganger.

As an impressionable youngster looking for heroes, I fell hard under the spell of the Garvey Mystique. I was not alone. He was also the favorite player of my brother, Michael, and most boys I knew. I never bothered getting his autograph before games because the crowd was always too big. By 1977, Garvey’s clean-cut image had elevated him to mega-role model status, resulting in a junior high school named after him in Lindsay, California. In 1978, he was the first player to rack up more than four million votes for the All-Star Game. Garvey repaid the fans by winning the All-Star MVP Award. He popped up in Aqua Cologne commercials and on Fantasy Island. He was crowned with a new nickname—“Senator”—a nod to the promising political career that no doubt loomed in his future. In 1981, he was included in a coffee-table book that I still have to this day: The 100 Greatest Baseball Players of All Time.

But behind the scenes, Garvey was dealing with his own kryptonite—teammates resentful of his popularity, troubles at home with his wife, Cyndy, and later, paternity suits brought against him after his own marriage dissolved.

There’s an old adage in baseball: “You’re only as good as your last at-bat.” The public’s lasting impression of Garvey was not the day he walked off the field as a San Diego Padre in May of 1987, but his admission that he fathered two children out of wedlock to two separate women in 1989. That same year, Cyndy, then his ex-wife, published a scathing tell-all book that exposed the alleged dark side of Steve Garvey.

I cannot overemphasize the repercussions all this had on Garvey’s legacy at that time. Overnight, he became a national punch line. (Anyone remember those “Steve Garvey Is Not My Padre” bumper stickers?) Garvey’s first year of eligibility for the Hall of Fame was in 1993. Needing 75 percent of the votes by the Baseball Writers Association of America for induction, Steve garnered just 41.6 percent. In 2007, his last year of eligibility, his vote count had shriveled to a paltry 21 percent.

So how did this “future Hall of Famer,” as he was so often referred to in his playing days, lose his Get Into Hall Free card? It’s a question many have pondered. I believe there are three main reasons why the Baseball Writers shut Garvey out of the Hall.

...

7th INNING:

February - May 1981

5-for-5: Five Games that Defined the 1981 Dodgers

#1—Fernandomania: Wild & Uncut! Dodger Stadium, April 27, 1981

Though Valenzuela came into his April 27 home start with a 4–0 record, three of those wins came on the road. You can imagine the pent-up energy going into this game. For most of the month, we had to watch Fernando make history from afar on our TV sets or through the radio. For his homecoming, Fernando lived up to his billing—and then some. I was not fortunate enough to attend this game, but luckily we all had the next best thing—Vin.

The game was scoreless until the bottom of the fourth inning. After getting two quick outs, starter Tom Griffin faced the bottom third of the order. Scioscia singled, and Russell kept the inning alive with a single to right, allowing Mike to go to third. That brought up the Dodgers’ best hitter so far on the year. Vin with the call:

Valenzuela singled in the third inning—the first Dodger hit. So of course now, Griffin has been warned. Valenzuela with five hits in his 13 at-bats. 1-for-1, hitting .385 . . . So Mike Scioscia at third, Bill Russell at first, with two out in the fourth. No score . . . Griffin at the belt, ready, delivers . . . Valenzuela lines it into right field, base hit! Dodgers lead, one-to-nothing!

As the crowd went into a frenzy, organist Helen Dell trotted out the “Paso Doble” theme you typically hear for the matador at a bullfight—“Tuh DUHHH . . . tuh duh duh duh duh DUHHH . . . tuh duh duh duh duh . . . DUH!” This would become a signature sound “drop” for the man they would call El Toro whenever he did something amazing.

Forty-one seconds later, Vin came back on:

And they are going wiiiiiiild at Dodger Stadium. There’s no way this game will continue, not for a while. Valenzuela is told by Manny Mota, ‘Take your helmet off!’ And Valenzuela said, “Okay!” He lifted his helmet high in the air, and the crowd loves it. I swear, Fernando, you are too much in any language. Can you imagine, on this night of all nights? He’s 2-for-2, he got the first Dodger hit, he just drives in a run, and the Dodgers lead, 1–0 . . . And here’s Davey Lopes. 0-and-1. Griffin ready and delivers, and it’s waved at and missed. Listen to this crowd just talking to themselves. [Laughs.] What a show!

Valenzuela’s hit opened the floodgates. Two singles later, the Dodgers led, 4–0.

Fernando, of course, wasn’t done at the plate. In the bottom of the sixth, he singled to left for his third hit of the day. He would close out the month of April with a .438 average. The Dodgers added another run in the seventh, and Fernando took a 5–0 lead into the ninth inning. He was on the verge of pitching his third consecutive shutout, his fourth in five starts.

Leadoff batter Larry Herndon greeted him with a single, but El Toro retired the next two batters on flyouts. This brought the crowd to its feet. And Jim Wohlford in to pinch-hit for the light-hitting Johnnie LeMaster.

Of course, it wasn’t just Fernando who was giving us goosebumps. Just as Da Vinci was inspired by the Mona Lisa, Vin was thoroughly relishing Fernando’s storybook season, and we were the lucky recipients.

That said, I am going to pause here to bestow my “True Blue Ribbon” call for the 1981 season.

And the 1981 “True Blue Ribbon” Call Goes To . . .

The maestro, of course! That’s right, the single greatest call during the regular season came with one out left in this April 27 game, with Wohlford at the plate, Fernando on the mound, and Vin behind the mic.

There is a common perception that Vin Scully’s finest hour as a broadcaster came when he called the final out of Sandy Koufax’s perfect game on September 9, 1965—particularly Sandy’s final battle with batter Harvey Kuenn. Considering the stakes, it’s hard to disagree—the clip is truly a masterpiece. But like Sandy’s perfect game, his final call of Fernando’s fifth win deserves to go down in the annals of his all-time calls. Vin put on a clinic for how to stage a historic moment, peppering his play-by-play with classic literary devices that add gravity to the moment without feeling stuffy or premeditated. Actually, that’s what makes it all the more brilliant—the fact that he did it all live, with no script to fall back on.

Here is Vin Scully calling Jim Wohlford’s complete at-bat against Fernando Valenzuela, which lasted 3½ minutes:

And with two out, Jim Wohlford will come off the bench and bat for Johnnie LeMaster.

Vin paused to let PA announcer John Ramsey set the stage:

Your attention please.

For the Giants.

Batting.

For LeMaster.

Number One.

Jim.

Wohlford.

Jim Wohlford is one of those guys who makes you wonder how he ever amassed a 15-year career. As a mostly corner outfielder, he wasn’t blessed with power or any real speed (he stole 17 bases in 1977, but was caught 16 times). The best you can say about him was that he didn’t strike out a lot. Coincidentally, my junior varsity baseball coach once told me that was my best asset, too, calling me “plucky”—right before cutting me from his team.

Back to Vin:

So here is Jim Wohlford, hitting .400. Right-hand batter. And this crowd now, on its feet. Theyyyyyy want to see it. Valenzuela, out of a stretch, the pitch to Wohlford . . . screwbaaaaaall for a strike!

The crowd roared, as they would for each strike. Vin used repetition—in this case, repeated usage of the word “more”—to build the moment, its emphasis establishing a neat rhythmic meter.

And every time Valenzuela gets on the rubber, more people stand, and more people cheer, and more people applaud. And the night is coming to the end that they had hoped for. The strike-one pitch . . . screwball, outside.

The crowd voiced its disapproval with plate umpire Fred Blocklander.

We had said it earlier, it really is too good to be true. A full house came to see him, and he has not disappointed a soul. The 1-1 . . .screwbaaaaaaaaall, is swung on and missed! One-and-two.

Vin returned to repetition, using “and” to link all the disparate moments of this at-bat into one unifying story that was building to its inevitable climax. If that wasn’t enough, he mixed in some Spanish and assonance.

And now you can hear it—the English cheers, and the Spanish “Zurdo! Zurdo!” [Southpaw.] And the applause . . . and there hasn’t been anything like it, anywhere, anytime. And Wohlford, the right-hand batter, waits, Valenzuela ready, the 1-2 . . . fastball missed . . . ball two.

More boos.

Two-and-two. And the Spanish phrase, they tell me, is “Se quita la gorra”—a tip of the cap. And that’s what this crowd wants to give Valenzuela now. The left-hander ready, and the 2-2 pitch . . . fastball fouled away.

Wohlford’s battle with Valenzuela reached the two-minute mark. Vin used the occasion to speak to not just the length of this game, but baseball’s unique ability to suspend us all in time.

It has taken almost three hours to get here. But baseball is the one sport that is not measured in time. Nobody cares that the run scored at a certain time. And no hitter has to worry that time is running out. Time doesn’t mean a darn thing here tonight. Here’s the 2-2 . . . fastball, hit foul. And Wohlford, a good hitter, still up there 2-and-2.

There is no one in the Giant on-deck circle. It’s against the rules. You’re supposed to have somebody out there. But the fact that the on-deck circle is empty might sum up the kind of mastery and spell that Valenzuela has cast so far tonight. He has shut out the Giants . . . he has two out in the ninth . . . he has 2-and-2 the count to Jim Wohlford . . . and the crowd is begging him to make one last pitch and call it a night.

...

The game was scoreless until the bottom of the fourth inning. After getting two quick outs, starter Tom Griffin faced the bottom third of the order. Scioscia singled, and Russell kept the inning alive with a single to right, allowing Mike to go to third. That brought up the Dodgers’ best hitter so far on the year. Vin with the call:

Valenzuela singled in the third inning—the first Dodger hit. So of course now, Griffin has been warned. Valenzuela with five hits in his 13 at-bats. 1-for-1, hitting .385 . . . So Mike Scioscia at third, Bill Russell at first, with two out in the fourth. No score . . . Griffin at the belt, ready, delivers . . . Valenzuela lines it into right field, base hit! Dodgers lead, one-to-nothing!

As the crowd went into a frenzy, organist Helen Dell trotted out the “Paso Doble” theme you typically hear for the matador at a bullfight—“Tuh DUHHH . . . tuh duh duh duh duh DUHHH . . . tuh duh duh duh duh . . . DUH!” This would become a signature sound “drop” for the man they would call El Toro whenever he did something amazing.

Forty-one seconds later, Vin came back on:

And they are going wiiiiiiild at Dodger Stadium. There’s no way this game will continue, not for a while. Valenzuela is told by Manny Mota, ‘Take your helmet off!’ And Valenzuela said, “Okay!” He lifted his helmet high in the air, and the crowd loves it. I swear, Fernando, you are too much in any language. Can you imagine, on this night of all nights? He’s 2-for-2, he got the first Dodger hit, he just drives in a run, and the Dodgers lead, 1–0 . . . And here’s Davey Lopes. 0-and-1. Griffin ready and delivers, and it’s waved at and missed. Listen to this crowd just talking to themselves. [Laughs.] What a show!

Valenzuela’s hit opened the floodgates. Two singles later, the Dodgers led, 4–0.

Fernando, of course, wasn’t done at the plate. In the bottom of the sixth, he singled to left for his third hit of the day. He would close out the month of April with a .438 average. The Dodgers added another run in the seventh, and Fernando took a 5–0 lead into the ninth inning. He was on the verge of pitching his third consecutive shutout, his fourth in five starts.

Leadoff batter Larry Herndon greeted him with a single, but El Toro retired the next two batters on flyouts. This brought the crowd to its feet. And Jim Wohlford in to pinch-hit for the light-hitting Johnnie LeMaster.

Of course, it wasn’t just Fernando who was giving us goosebumps. Just as Da Vinci was inspired by the Mona Lisa, Vin was thoroughly relishing Fernando’s storybook season, and we were the lucky recipients.

That said, I am going to pause here to bestow my “True Blue Ribbon” call for the 1981 season.

And the 1981 “True Blue Ribbon” Call Goes To . . .

The maestro, of course! That’s right, the single greatest call during the regular season came with one out left in this April 27 game, with Wohlford at the plate, Fernando on the mound, and Vin behind the mic.

There is a common perception that Vin Scully’s finest hour as a broadcaster came when he called the final out of Sandy Koufax’s perfect game on September 9, 1965—particularly Sandy’s final battle with batter Harvey Kuenn. Considering the stakes, it’s hard to disagree—the clip is truly a masterpiece. But like Sandy’s perfect game, his final call of Fernando’s fifth win deserves to go down in the annals of his all-time calls. Vin put on a clinic for how to stage a historic moment, peppering his play-by-play with classic literary devices that add gravity to the moment without feeling stuffy or premeditated. Actually, that’s what makes it all the more brilliant—the fact that he did it all live, with no script to fall back on.

Here is Vin Scully calling Jim Wohlford’s complete at-bat against Fernando Valenzuela, which lasted 3½ minutes:

And with two out, Jim Wohlford will come off the bench and bat for Johnnie LeMaster.

Vin paused to let PA announcer John Ramsey set the stage:

Your attention please.

For the Giants.

Batting.

For LeMaster.

Number One.

Jim.

Wohlford.

Jim Wohlford is one of those guys who makes you wonder how he ever amassed a 15-year career. As a mostly corner outfielder, he wasn’t blessed with power or any real speed (he stole 17 bases in 1977, but was caught 16 times). The best you can say about him was that he didn’t strike out a lot. Coincidentally, my junior varsity baseball coach once told me that was my best asset, too, calling me “plucky”—right before cutting me from his team.

Back to Vin:

So here is Jim Wohlford, hitting .400. Right-hand batter. And this crowd now, on its feet. Theyyyyyy want to see it. Valenzuela, out of a stretch, the pitch to Wohlford . . . screwbaaaaaall for a strike!

The crowd roared, as they would for each strike. Vin used repetition—in this case, repeated usage of the word “more”—to build the moment, its emphasis establishing a neat rhythmic meter.

And every time Valenzuela gets on the rubber, more people stand, and more people cheer, and more people applaud. And the night is coming to the end that they had hoped for. The strike-one pitch . . . screwball, outside.

The crowd voiced its disapproval with plate umpire Fred Blocklander.

We had said it earlier, it really is too good to be true. A full house came to see him, and he has not disappointed a soul. The 1-1 . . .screwbaaaaaaaaall, is swung on and missed! One-and-two.

Vin returned to repetition, using “and” to link all the disparate moments of this at-bat into one unifying story that was building to its inevitable climax. If that wasn’t enough, he mixed in some Spanish and assonance.

And now you can hear it—the English cheers, and the Spanish “Zurdo! Zurdo!” [Southpaw.] And the applause . . . and there hasn’t been anything like it, anywhere, anytime. And Wohlford, the right-hand batter, waits, Valenzuela ready, the 1-2 . . . fastball missed . . . ball two.

More boos.

Two-and-two. And the Spanish phrase, they tell me, is “Se quita la gorra”—a tip of the cap. And that’s what this crowd wants to give Valenzuela now. The left-hander ready, and the 2-2 pitch . . . fastball fouled away.

Wohlford’s battle with Valenzuela reached the two-minute mark. Vin used the occasion to speak to not just the length of this game, but baseball’s unique ability to suspend us all in time.

It has taken almost three hours to get here. But baseball is the one sport that is not measured in time. Nobody cares that the run scored at a certain time. And no hitter has to worry that time is running out. Time doesn’t mean a darn thing here tonight. Here’s the 2-2 . . . fastball, hit foul. And Wohlford, a good hitter, still up there 2-and-2.

There is no one in the Giant on-deck circle. It’s against the rules. You’re supposed to have somebody out there. But the fact that the on-deck circle is empty might sum up the kind of mastery and spell that Valenzuela has cast so far tonight. He has shut out the Giants . . . he has two out in the ninth . . . he has 2-and-2 the count to Jim Wohlford . . . and the crowd is begging him to make one last pitch and call it a night.

...

9th INNING:

October 1981

True-Blue Monday: NLCS-Game 5 (Olympic Stadium)

It was time to resort to Plan B—Operation: T.R. (Transistor Radio). The mission was simple: Set radio volume to its lowest setting. Smuggle radio into backpack. Lay backpack on desk. Press ear against backpack.

It would be like those nights of listening to games under my pillow. Only, in this situation, it would be done in broad daylight, in a small classroom, under the prying eyes of a teacher. The risk of getting caught lay somewhere between “definite” and “what’re you—crazy?” But it had to be done.

It remained 1–1 through seven innings, with Fernando retiring 19 out of 20 at one point. The final innings just happened to coincide with the start of my geometry class, taught by a humorless ramrod named—and I’m not making this up—Mr. Bland.

I would’ve felt a little guilty about my ruse if it was against a teacher I liked. But Mr. Bland did not endear himself to anybody with his condescending attitude. Just a week before, a student in the front row seeking some untold payback purposely spilled some blue pen ink on a desk Mr. Bland sometimes sat on to get off his feet for a while. Predictably, Mr. Bland hoisted his posterior onto the puddle of fresh ink, then got up to write on the chalkboard. We spent the next half hour biting our lower lips and turning purple, trying to stifle laughs as we gazed at the blue blob hitching a ride on the cheeks of his khakis.

There were three rows of desks in our classroom, and I strategically positioned myself in the back row, behind the tallest kid in class. Two desks to my left sat my friend, Andrew, whose Dodger devotion rivaled mine. Andrew had also brought a transistor radio to class and stashed it in his backpack. Redundancy would be essential. If one of us got busted, the other could still relay signals.

As usual, Mr. Bland spent much of the period with his back to the class, jotting mind-numbing formulas on the board, giving us ample windows to bend our heads toward backpacks. I was having a hard time tuning in to KABC, but Andrew wasn’t. He updated me on every at-bat by passing notes to me through a complicit student who sat between us. In the top of the eighth, I received Andrew’s first missive:

Lopes, 1B.

I immediately wrote back:

How many out?

Andrew flashed one finger. I nodded, and Andrew pressed his ear against his backpack again. After a few moments he grinned and jotted another note through our intermediary:

Lopes SB!!!

My heart, already racing due to our crazy stunt, beat even faster against my chest. I tried to get a read on the next play off of Andrew’s expressions. Why was he taking so long to write his next note? Maybe Bill Russell singled him in! It felt like we were two prisoners exchanging intelligence, although in hindsight the fragmentary way in which I was receiving reports for each at-bat was kind of like a primeval version of those auto-updates you get online at ESPN.com or MLB Live.

Mr. Bland briefly addressed the class again, then turned toward the board. Andrew scribbled a hurried message:

Russell ground ball.

Lopes out, rundown.

#@^$#%&!

I replied with my own expletive. Baker grounded out to end the inning and the Dodgers blew their chance to go ahead. Other students turned in their seats to mouth, “What’s the score?” or “What’s going on?” A low murmur spread throughout the class.

I sensed that Mr. Bland may have been catching on. He refused to turn toward the board for the next five minutes and seemed to be casting a suspicious eye on the back row, though it may have just been my paranoia. The entire bottom of the eighth inning passed without Andrew or me knowing that Fernando was dispensing of the Expos in order.

As the top of the ninth inning got underway, with the score still 1–1, Mr. Bland returned to the chalkboard to jot out a new sequence of formulas, and I renewed my efforts to tune in to the game. Through a bunch of static, I was just able to catch Jerry Doggett’s familiar baritone. Steve Rogers had come in to replace Ray Burris and had just gotten Garvey to pop out to start the inning. One out and Cey at the plate.

The next couple of minutes were incredibly nerve-wracking. My right ear, pressed against my backpack, followed each pitch of Cey’s at-bat, while my left ear was on the “look-out” for any changes in Mr. Bland’s voice amidst his droning geometric equations, the two stimuli comingling uncomfortably in my head like a talk-radio station trying to drown out another one playing music:

“Here we have alternate interior angles . . . ”

1-and-1 to Cey . . .

“ Which creates a null set . . . ”

Two balls and one strike . . .

“Triangle ABC . . . ”

Three-and-one now . . .

“Triangle DEF . . . ”

Fly ball to left field . . .

“Hypotenuse . . . ”

Two outs . . .

“The result would be incongruent . . . much like someone putting their head against a backpack to listen to the radio.”

I lifted my head. Mr. Bland was staring daggers at me.

Oops.

...

It would be like those nights of listening to games under my pillow. Only, in this situation, it would be done in broad daylight, in a small classroom, under the prying eyes of a teacher. The risk of getting caught lay somewhere between “definite” and “what’re you—crazy?” But it had to be done.

It remained 1–1 through seven innings, with Fernando retiring 19 out of 20 at one point. The final innings just happened to coincide with the start of my geometry class, taught by a humorless ramrod named—and I’m not making this up—Mr. Bland.

I would’ve felt a little guilty about my ruse if it was against a teacher I liked. But Mr. Bland did not endear himself to anybody with his condescending attitude. Just a week before, a student in the front row seeking some untold payback purposely spilled some blue pen ink on a desk Mr. Bland sometimes sat on to get off his feet for a while. Predictably, Mr. Bland hoisted his posterior onto the puddle of fresh ink, then got up to write on the chalkboard. We spent the next half hour biting our lower lips and turning purple, trying to stifle laughs as we gazed at the blue blob hitching a ride on the cheeks of his khakis.

There were three rows of desks in our classroom, and I strategically positioned myself in the back row, behind the tallest kid in class. Two desks to my left sat my friend, Andrew, whose Dodger devotion rivaled mine. Andrew had also brought a transistor radio to class and stashed it in his backpack. Redundancy would be essential. If one of us got busted, the other could still relay signals.

As usual, Mr. Bland spent much of the period with his back to the class, jotting mind-numbing formulas on the board, giving us ample windows to bend our heads toward backpacks. I was having a hard time tuning in to KABC, but Andrew wasn’t. He updated me on every at-bat by passing notes to me through a complicit student who sat between us. In the top of the eighth, I received Andrew’s first missive:

Lopes, 1B.

I immediately wrote back:

How many out?

Andrew flashed one finger. I nodded, and Andrew pressed his ear against his backpack again. After a few moments he grinned and jotted another note through our intermediary:

Lopes SB!!!

My heart, already racing due to our crazy stunt, beat even faster against my chest. I tried to get a read on the next play off of Andrew’s expressions. Why was he taking so long to write his next note? Maybe Bill Russell singled him in! It felt like we were two prisoners exchanging intelligence, although in hindsight the fragmentary way in which I was receiving reports for each at-bat was kind of like a primeval version of those auto-updates you get online at ESPN.com or MLB Live.

Mr. Bland briefly addressed the class again, then turned toward the board. Andrew scribbled a hurried message:

Russell ground ball.

Lopes out, rundown.

#@^$#%&!

I replied with my own expletive. Baker grounded out to end the inning and the Dodgers blew their chance to go ahead. Other students turned in their seats to mouth, “What’s the score?” or “What’s going on?” A low murmur spread throughout the class.

I sensed that Mr. Bland may have been catching on. He refused to turn toward the board for the next five minutes and seemed to be casting a suspicious eye on the back row, though it may have just been my paranoia. The entire bottom of the eighth inning passed without Andrew or me knowing that Fernando was dispensing of the Expos in order.

As the top of the ninth inning got underway, with the score still 1–1, Mr. Bland returned to the chalkboard to jot out a new sequence of formulas, and I renewed my efforts to tune in to the game. Through a bunch of static, I was just able to catch Jerry Doggett’s familiar baritone. Steve Rogers had come in to replace Ray Burris and had just gotten Garvey to pop out to start the inning. One out and Cey at the plate.

The next couple of minutes were incredibly nerve-wracking. My right ear, pressed against my backpack, followed each pitch of Cey’s at-bat, while my left ear was on the “look-out” for any changes in Mr. Bland’s voice amidst his droning geometric equations, the two stimuli comingling uncomfortably in my head like a talk-radio station trying to drown out another one playing music:

“Here we have alternate interior angles . . . ”

1-and-1 to Cey . . .

“ Which creates a null set . . . ”

Two balls and one strike . . .

“Triangle ABC . . . ”

Three-and-one now . . .

“Triangle DEF . . . ”

Fly ball to left field . . .

“Hypotenuse . . . ”

Two outs . . .

“The result would be incongruent . . . much like someone putting their head against a backpack to listen to the radio.”

I lifted my head. Mr. Bland was staring daggers at me.

Oops.

...